The Radiance of Virtue: Beauty, Character, and the Moral Imagination.

Beauty and character are frequently treated as if they belong to separate realms — the former to the eye, the latter to the conscience — yet this division is artificial. In live experience, beauty and personality are entwined in a subtle dialectic: outward appearance may arrest attention, but it is inner quality — kindness, confidence, integrity, authenticity — that secures lasting reverence. What merely pleases the eye is fleeting; what moves the soul endures. All that glitters is not gold.

From a philosophical standpoint, the persistent

confusion between beauty and goodness is an old but resilient error. To equate

physical beauty with moral worth is to mistake the surface of the river for its

depth. History and daily life alike remind us that beautiful people are not

always good. Still, good people, in a deeper sense, are always beautiful —

their beauty, rooted in inner virtue, such as compassion or honesty, commands

lasting respect and admiration.

It is therefore a profound delusion to believe that

beauty itself constitutes goodness. The absence of a visible flaw, when

detached from virtue, becomes a flaw of its own: an emptiness polished to

perfection. Classical aesthetics warns us here. Beauty, stripped of ethical

substance, risks becoming sterile — an object to be consumed rather than a

force that transforms. To admire without being changed is not to encounter

beauty at all; it is merely to observe form.

True beauty demands more than sight. It asks for

feeling, for disturbance, for participation. A work of art, a human life, or a

social ideal cannot be fully known by inspection alone; it must affect us,

unsettle us, enlarge us. Beauty that does not call forth reflection or

responsibility is cosmetic, not consequential. Genuine beauty has the power to

inspire change and growth within us.

Socially, this understanding carries urgent

implications. In an age governed by images, metrics, and curated appearances,

societies risk privileging spectacle over substance. When surface beauty is

rewarded without regard for character, the social fabric thins; empathy erodes,

and unity becomes performative rather than practised. Recognising inner virtue

as a universal form of beauty can foster cross-cultural appreciation of moral

character, emphasising shared human values over superficial differences. This

awareness encourages us to feel responsible for nurturing genuine virtues in

society.

Thus, beauty rooted in character becomes not merely

personal but political. It gestures toward peace, unity, and love — not as

sentimental abstractions, but as lived commitments. These are the indispensable

ingredients in what might be called the global sauce of peace and development:

a slow, patient mixture requiring virtue more than vanity, depth more than

display. Recognising this can inspire us to see moral virtue as a guiding force

for collective progress.

Therefore, beauty is not something we possess; it is

something we enact. It is revealed not in how closely one approximates an ideal

image, but in how faithfully one embodies humane values. Where character

flourishes, beauty follows — quietly, insistently, and with the power to remake

both hearts and societies. This invites one to see one's own actions as vital

in shaping genuine beauty and moral virtue.

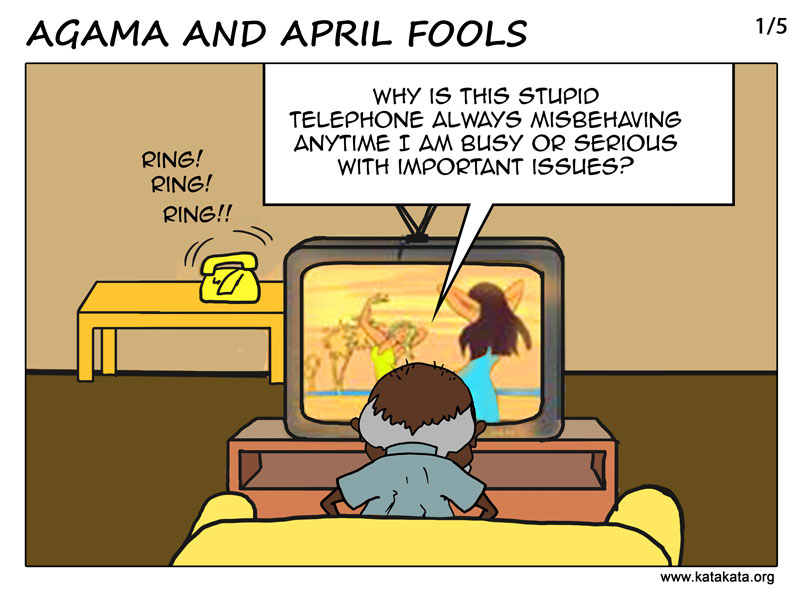

Video: https://www.youtube.com/shorts/mUsXwwdUS80

For

unrestricted access to Kata Kata content, subscribe to our platform: katakata.org/mainmenu