Gender Discrimination and Rights Violations: Nigerian University’s ‘No Bra, No Exam’ Policy Sparks Outrage.

A Nigerian university is facing intense public backlash after a viral video revealed female students were subjected to physical checks to determine if they were wearing bras before being allowed into an examination hall — a practice widely condemned as discriminatory, invasive, and emblematic of broader gender inequality in institutional policy.

The embarrassing video footage showing female staff patting down women's chests in queues outside an exam venue was shot at Olabisi Onabanjo University in Ogun State. What followed was national outrage and severe debates over gendered dress codes, bodily autonomy and gender discrimination in general in institutions of learning around the country. Defenders of the practice argue it is part of a long-standing dress code intended to preserve a "distraction-free" academic environment. However, critics say the policy is deeply sexist, rooted in patriarchal ideas about female modesty and male discipline — and enforced through means bordering on sexual harassment.

"Unwarranted

physical contact is a violation," said Haruna Ayagi, a senior official

with the Human Rights Network. "This approach is not only wrong, it opens

the university to legal consequences. It violates the rights of women and

reinforces a system of gender-based control." This violation of rights

should not be overlooked; it's a call to action.

Though the university is a public, secular institution, students say it imposes a rigid moral code that disproportionately targets women. One female student, speaking anonymously, described a climate of constant surveillance: "We are always being watched, judged for what we wear. It feels less like a university and more like moral policing."

The students'

union president, Muizz Olatunji, attempted to justify the rule on X (formerly

Twitter), explaining that the university promotes a dress code

"encouraging modesty" and "respectful" attire. However, the

code — which bans clothing "capable of making the same or opposite sex to

lust" — appears to place responsibility for others' behaviour squarely on

women's bodies.

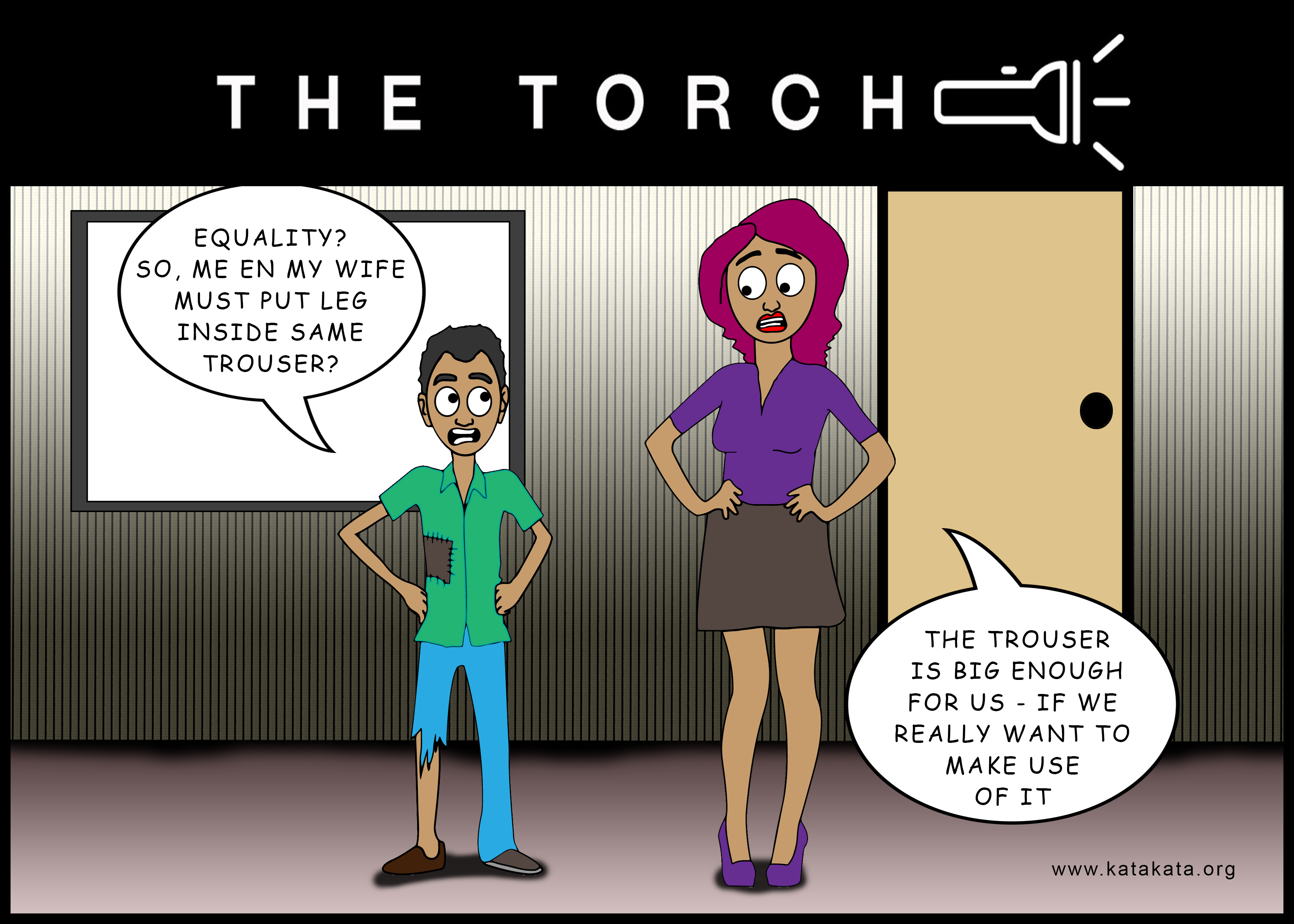

For those who

support the school action and gendered dress code, such a stand can only stand

the test of security and fairness if the same principle applies to men.

Unfortunately, this is hardly the case. That is where the danger of double

standards comes into play. When men are presumed unable to control their sexual

urges, while women are expected to regulate their bodies to avoid provoking

men, it inherently reduces women to sex objects and women to sex predators. It

automatically gives men the right to have control over women and their

sexuality. This framing not only objectifies women but also infantilises men.

This kind of sexist policy leads to institutionalised sexism and reinforces the

psychology of gender, forcing female students to uphold moral standards while

male behaviour is excused or overlooked.

Sadly, the

"no bra, no exam" rule normalises the policing of women's bodies and

reinforces a culture in which women are seen not as equal participants in

education but as potential distractions, defined primarily through their

sexuality. The dichotomy comes with dire repercussions, including causing

unnecessary gender consciousness and pressure on women and reducing women's

academic experience and qualifications solely on a 'modest' dress code and

appearance.

The result of such

patriarchal control on women through institutionalisation by the university

reinforces gender and sex-role internalisation, which may lead to an

inferiority complex and feelings of guilt and shame. Those feelings

unconsciously lead female students to believe they are inferior to their male

counterparts, a perception that may seriously impact their academic

performance. When a group of students, in this case, female students, are led

to believe that their bodies are a distraction and unconducive to learning,

which must be hidden, they generally accept this and act accordingly. This

mindset erodes self-worth, confidence and dignity in women and gives males

excuses to treat them as inferior in their relationship. Treating women as

potential sources of moral decay or as objects of temptation dehumanises them,

reducing their presence in academic spaces to something to be controlled rather

than celebrated. In this way, such policies not only fail to promote discipline

or decorum — they entrench a culture of discrimination, surveillance, and

misogyny.

Rights activists

and students alike are calling for an urgent review of the university's

policies, with demands for accountability, gender sensitivity training, and a

complete halt to body inspections. This is not just a request; it's a necessity

for change. Sadly, with such a 'No Bra, No Exam' discriminatory policy, Olabisi

Onabanjo University, which was founded in 1982, is now under scrutiny for

policies that, rather than promote academic excellence, seem to entrench

institutionalised sexism. It is time for the university to erase the ugly image

to avoid further damage to its educational programs and reputation.